Question 15: What does it mean to say that Christ is the redemptive word of God?

Answer: Christ, as the redemptive word of God, is God’s word spoken to us that we may be raised from our state of spiritual and bodily death, and may have life, and life abundant, in fellowship with God.

Question 16: What is God’s redemptive revelation?

Answer: The redemptive revelation of God is his saving revelation of himself, formerly through various acts, words, appearances, and symbols, and finally and ultimately culminating in the incarnate word himself: Jesus Christ.

Question 17: How can we know Christ?

Answer: Christ is to be known today through the reading, preaching, and teaching of the Word of God, as he is revealed in the scriptures of the Old and New Testaments. In this way, by the ministry of the Holy Spirit, Jesus Christ is continually preached and speaks that we may have life and life abundant.

Before our first parents fell (Gen 3), they enjoyed the privilege of a direct verbal revelation from God (e.g. Gen 2:15-17). That is to say, God spoke directly to them. So we see, then, that right from the start God’s “primary vehicle of truth” was words (Tripp, War of Words, p.8). This is why we must go to such lengths to unfold the nature and implications of the word of God as we study the truth of God. God used and uses words to communicate with people.

Now, it is clear from the pre-fall condition that this “special” kind of revelation on God’s part provided the necessary light to Adam and Eve for understanding and engaging with God’s natural revelation. I say “special” at this point because that’s the word theologians use most often. As God spoke to them, his word of Special Revelation was what made sense of the world for them. Van Til expresses this thought nicely:

“Before the fall, it was through the direct positive revelation of God with respect to nature and himself that man learned the highest final purposes with respect to both. It was through the direct positive revelation of God that man learned the fact that he should die if he ate of the fruit of the forbidden tree, with the implication that he should live forever with God if he would obey the voice of God. The highest revelation with respect to nature and man set all the other knowledge that man had of nature and himself into a new and more brilliant light. It made of nature the setting for the highest moral activities of God with respect to man” (Van Til, Systematic Theology, p.84).

After the fall, mankind was severed from any positive relationship with God. We had declared war upon our maker, and the inevitable result was that we now lived under the dark clouds of his wrath. Ephesians 2:3 describes mankind as being “children of wrath” for this reason. We became darkened in our understanding, as Morris says, “the divine is not known to men” (Morris, I Believe in Revelation, p.17). The first five chapters of the Book of Romans are perhaps the clearest and fullest doctrinal presentation of these facts in all of Scripture, and you should re-read them if you are not very familiar with them. 1 Cor 2:14 also says that in our naturally fallen state we cannot grasp the spiritual reality of knowing God. The narrative of Genesis 3-11 likewise bears out this hardened rebellion that beats strong in the heartbeat of humanity.

Because we were spiritually dead and now subject to God’s wrath, any positive revelation from God would thus have to take on a redemptive character. In other words, if God was to commune with us again, he would have to redeem us, he would have to speak a word of redemption into his fallen creation. The purpose of special revelation after the fall, says Warfield, is “to rescue broken and deformed sinners from their sin and its consequences” (Warfield, Inspiration, p.74).

After Adam and Eve fell, God actually did this. He continued to speak to fallen humanity, his words were laden with grace and conditioned by his promise of redemption. Genesis 3:15 contains the first hint, and by Genesis 12:1-3 we have a full blown revelation of God’s intention to bring blessing and redemption to humanity through the family of Abraham. Now it’s interesting, isn’t it, that in Galatians 3:8 the Apostle Paul says that this word to Abraham, way back in Genesis 12, was actually the message of the gospel of Jesus Christ. What this means is that, since the time when humanity fell, God’s revelation of himself to people has been a redemptive revelation, and that revelation is the message of Jesus’ gospel. Jesus is the final Word of God (Jn 1:1) for a fallen humanity (Heb 1:1-3), the only way of salvation (Acts 4:12). The Gospel of John gives the stark image of light shining into darkness – that’s what Jesus was and is to the world: a revelation of redemptive light shining into darkness, the Word of God incarnate. He always has been – right from Abraham and before. There was never a redemptive b-plan, Jesus was and always has been it.

So here’s where we’ve landed: Jesus is God’s Word of redemption, his personal revelation of himself to a fallen humanity. Someone might point out in response to this that Jesus didn’t show up in history until centuries after the events of Genesis 3. Does that mean that humanity prior to Christ’s incarnation was doomed to death, without access to God’s redemptive word for them? In response to this, it’s helpful to consider that B.B.Warfield, the great Princetonian, spoke of special revelation as a “Process,” a process that was “gloriously completed in Christ” (Warfield, Inspiration, p.79). Warfield was dead right. So let’s talk about this process and open it up a little.

In Hebrews 1:1 we read exactly what Warfield just concluded, that God spoke “at many times and in many ways to our fathers by the prophets” in former times, “but in these last days he has spoken to us by his son.” If you want the full treatment on this, then an in depth study of the whole Old Testament will yield abundant fruit! Our space is somewhat more limited, so I’ve asked Dr Morton H. Smith to be a tour guide and show us the broad contours of how Christ was spoken of and revealed through the history of the Old Testament and in the words of the prophets. In Smith’s little-known work of Systematic Theology, he gives us a thorough yet precise (and very useful) biblical survey of this “process” of revelation that Warfield spoke of (Smith, Systematic Theology Vol 1, 39-67). He traces it right through Scripture. I would highly commend that section of Smith’s book to your reading if you can get ahold of it,1 but here’s what I gleaned at any rate.

Like most theologians worth their salt, Smith uses the two major categories of revelation: “Natural revelation is that which comes through created reality, both within and without man. Supernatural revelation refers to that which is revealed outside of nature.” These are the two major categories of revelation you’ll hear most reformed theologians using.2 In general I prefer to modify these categories somewhat. It’s not that I don’t agree with them, I think they’re accurate, it’s just that if we jiggle our categories around a little, I think we can use our language to reflect a more helpful and clear notion of revelation overall.

So what Smith calls “supernatural revelation” (or “special revelation” by others), I am going to be calling “redemptive revelation.” Again, substantively we’re talking about the same thing. I don’t disagree with Smith’s position, I just choose to rename “supernatural revelation” to “redemptive revelation” because, as I have said (and Warfield… and Bavinck3), I think that the concept of redemption is the essential principle of this mode of revelation – more so than its “supernatural” or “special” character. “Special” isn’t a particularly sharp word after all, is it? It raises the question: Well, what’s so special about it? Why not dump “special” and replace it with the actual thing that is special? (i.e. redemption). Besides, I don’t find the stark contrast between “natural” and “supernatural” (which Smith’s distinction of supernatural & natural kind of assumes, or at least unhelpfully tends to suggest) to be all that biblical to begin with. Clearly there is a distinct natural order that God has made, but that order is not somehow antithetical to or radically separated from God’s supernatural acts in history. Anyway, with those distinctions in mind, let’s see what Smith has to say about redemptive revelation. Let the tour begin!

According to Smith, the Bible teaches us that redemptive revelation has come to us in four ‘modes’ throughout history: i) act; ii) word;4 iii) theophany;5 and iv) symbol. We will see shortly how all four modes are fulfilled in and culminate in Jesus Christ. So let’s take the tour and see just what the Bible shows us about these four modes.

Beginning with natural revelation (which we’ve already talked about), Smith says that creation itself is a revelational act. As an act of revelation, man’s entire existence and thought-world exists in a total environment of revelation. That’s its context. So far so good, this is revision for us at this point.

After the fall, man was “no longer fit” for communion with God. His condition is now one of alienation. God nonetheless graciously continues to communicate, and God’s direct, “supernatural” revelation then becomes redemptive in character (as we’ve already mentioned). This is clearly seen in the first promise of the gospel embedded in Genesis 3:15, which is part of God’s first redemptive revelation to mankind post-fall.

During the patriarchal period,6 scripture records a continual development of God’s redemptive revelation in all four modes. You’ve got acts of God (e.g. God sends a supernatural terror upon Jacob’s enemies to protect him and his family – Gen 35:5); words from God (e.g. God speaks to Abraham telling him not to sacrifice Isaac – Gen 22:11-12); theophany (e.g. when God turned up to wrestle with Jacob – Gen 32:22-32); and symbol (e.g. when God gave covenantal symbols to Abraham – Gen 15:17-18). Vos notes of this period that “…revelation, while increasing in frequency, at the same time becomes more restricted and guarded in its mode of communication. The sacredness and privacy of the supernatural begin to make themselves felt” (Vos, Biblical Theology, 82). In other words, the focus of God’s revelation was mostly reserved for what he was doing through the Jewish Patriarchs and their family.

In the Mosaic period, the three main forms of revelation (act, word, theophany) continue and intertwine, with theophany taking on a more permanent dimension (e.g. the pillar of cloud). Smith notes, in relation to word-revelation, that “The need for messengers to mediate the verbal communications of God to man gave rise to the office of the prophet” (p.52). He also helpfully notes that miracles, as acts of revelation, “have as their foundation and backdrop the work of creation and providence” (p.53). Moses himself was singularly unique in Israel’s history (Dt 34:10-12), and the revelation given through him was the foundation of the revelational building of the rest of the Old Testament and, indeed, of the new. We see symbolic revelation in the sacrificial system and the Aaronic priesthood.

We also see in this period a new dimension to God’s word-revelation: the words of God were recorded. Moses himself kept a written record in the first five books of the Old Testament, and we now see that God’s word revelation became both verbal and written in nature. This extension of verbal word revelation to written word revelation was clearly recognized by Jesus when he said to the Sadducees: “have you not read what was spoken to you by God?” (Mt 22:29-32). Through Moses, the written word of God was thus first equated with the spoken word of God, and the two would be intertwined throughout history from that point on (White, Scripture Alone, p.61).

Indeed, as Beeke & Smalley helpfully point out, God’s desire in recording the prophetic words in writing was to provide his people with a written rule and direction, he wanted these words to “shape their domestic and civil life” (Dt 31:10-13), he wanted them to be a “people of the Book” (Beeke & Smalley, ST Vol 1, p.320). The way that the scriptures frequently present themselves as the direct word of God is another scriptural proof clearly demonstrating the validity of the written mode of prophetic revelation. In the Old Testament, for example, phrases such as “thus says the LORD,” “the LORD said,” “the word of the LORD came to,” “Hear the word of the LORD,” etc. occur over 3,800 times… These phrases recur so extensively that it may accurately be stated that the primary theme of the Old Testament is that God speaks to people” (Fugate, God’s Word’s to you, p.105-6).

From Moses’ time to the end of the Old Testament (the post-Mosaic, or prophetic period), the prophetic word became the “chief mode of revelation” (p.55). Moses anticipated this in Dt 18:18. Smith notes that “…the prophet is the spokesman for God. This does not always involve telling the future. It does involve being an authoritative spokesman with an authoritative message from the living God” (p.56). The relationship between the offices of king and prophet was integral. Vos again notes that “(the office of prophet) marks the religion of the O.T. as a religion of conscious intercourse between Jehovah and Israel, a religion of revelation, of authority, a religion in which God dominates, and in which man is put into the listening, submissive attitude” (Vos, BT, p.211-212). The written word of God continued to unfold as well, the prophets both spoke and wrote, and slowly but surely the books of what we now have in the canon of scripture were formed.

Now it’s important to say at this point that all four modes of revelation used in the OT were incomplete. Theophanies were temporary, prophecy anticipated something that had not yet come, and miraculous acts amounted to no ultimate achievement in and of themselves as Israel declined. The OT revelation remains incomplete, all pointing forward to a completion in revelation that was still coming (Heb 11:39-40). As we later study the nature of the scriptures themselves, we will see very clearly that the entire OT order was pointing towards something else that was to come (much, much more on this later).

In short, it is Christ who brings this completion to God’s revelation. We see this as we consider how he relates to Smith’s four modes of revelation:

Acts revelation: First, Smith says, “His incarnation, atonement, resurrection and ascension are the great saving acts of God. These are the principal acts of regaining the paradise that Adam had lost” (p.64). These are the central acts of God that would save his people and redeem the world. John 1 and Hebrews 1:1-2 show this clearly.

Word revelation: Secondly, he is “the climax of prophetic revelation” (p.63). The prophets pointed to Him (1 Pt 1:10-11); he is the prophet promised by Moses (Dt 18:18; Ac 3:22); and he is the personal Word of God to us (Jn 14:6; 17:17). Naturally all word revelation in written form testifies to Christ as well (Lk 24:27; Jn 5:39). Whereas the Holy Spirit who inspired the prophets (2 Pt 1:21) came upon prophets momentarily in times past (e.g. Num 24:2; Is 8:11), the Spirit was upon Christ without measure (Jn 3:34). Christ likewise attested to the fact that his own words “shall never pass away” (Mt 24:35).

Theophony revelation: Thirdly, we should see that the incarnation was the crown of all theophonic revelation. In Christ, we see God with us (Is 7:14), even as Christ said: “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9).

Symbolic revelation: Finally, symbolic revelation – such as the sacrificial system – was all symbolic of the Christ to whom it pointed. Symbolic revelation, then, finds ultimate reality in symbolizing Christ and his work. Without that, it’s empty and meaningless. The sacraments of the New Testament are new forms of symbolic revelation that he gave to us. They point back to Christ’s death, and look forward to Christ’s return, representing the benefits of Christ’s work for us. As with previous symbolic revelation, they are Christo-centric.

In the apostolic age, the Apostles were appointed to bear witness to Christ, God’s final revelation (Heb 1:2) in an authoritative and unique way (Eph 2:20; 3:5).7 As Morris said: “…it was the apostles and not someone else who bore the definitive witness to what Jesus did for men” (Morris, Revelation, 30). We see verbal revelation in this period through the Apostles (2 Pt 3:16), but also through regular disciples having the gift of prophecy (1 Cor 14:1). We see miracles continuing as authenticating signs to the apostles, and we also see a few cases of theophany – no longer of clouds etc., but of Jesus the ultimate theophany (e.g. Stephen at his death, Paul on the road to Damascus, John on the Isle of Patmos). As mentioned, even symbolic revelation continues through the sacraments of Baptism and the Lord’s Supper. In other words, a variety of revelational modes continued after Christ’s ascension, but all revelation maintained its Christocentric nature and focus.

The prophetic word ministry of the Apostles, like that of the Old Testament prophets, also extended to a written prophetic word. Peter attested to Paul’s letters as being on par with the Old Testament Scriptures (2 Pt 3:16), and the Apostles knew also that what they spoke and penned was not their own words, but those of “Christ speaking” in them (1 Cor 14:37; 2 Cor 13:3).

There is plenty of “juice” in Smith’s outline. In fact, I would call it a tour de force in the concept of revelation throughout the Bible. You’ll notice that Smith thinks of Christ as the completion of all the various types of special revelation. This is a thoroughly biblical conclusion which, again, is stated quite clearly in Hebrews 1:2. So then, Smith lands where I started: God’s Word of redemptive revelation is Jesus Christ.

Now. Let’s summarise what we’ve said so far by attempting to answer our original question: Q. How does God reveal himself and his works to us so that we can know him? Answer? In two ways. First, through his creative and sustaining work of natural revelation; and second, through his redemptive revelation in Jesus Christ. We defined natural revelation earlier: Natural Revelation is a creative, sustaining act of God in which he clearly and authoritatively reveals himself and his works to all men through the natural, created order, so that his people can worship, glorify, enjoy, love, know, and serve him in it. If we had to define “redemptive revelation” we might say:

The redemptive revelation of God is his saving revelation of himself, formerly through various acts, words, appearances, and symbols, and finally and ultimately culminating in the Incarnate word himself: Jesus Christ.

An important question follows on from our findings here, and this really is where the rubber hits the road for us: How can we know Christ? This is the basic question of application in this area of theology. If we need a redemptive revelation from God, and he has made that revelation through Christ, it is crucial that we now ask: How can we know Christ? I’ve given the answer in Question 17 - it is through the Bible, the Word of God, that Christ is revealed and now speaks. The scriptures are the voice of Christ in the Church and the world, and our knowledge of Christ is inseparably tethered to the scriptures of the Old and New Testaments.

Here is where we’ve basically landed: we are a sinful race, and to save us from our sins God has revealed himself to us in the person of Jesus Christ. Now, one might ask in response to that: How then can I know Jesus Christ? He’s been dead for 2000 odd years now right? Well, no, he has not been dead (more on that later), but yes – it has been 2000 years or so since he was here bodily on earth. The question for us, then, is: How can we directly experience communion with God if we don’t have access to God’s redemptive revelation in Jesus Christ? Here’s the thing though: we do have access to Jesus. Not in the same way that people did when he walked here on this earth, but still we do have a personal connection with him available to us. He yet walks in the midst of his churches (Rev 2:1), and actually we have it better now than his disciples who were with him when he was on earth (although we do not have it better than we will in the new creation… but that’s getting way ahead of myself in the scheme of theology!).

But the question remains: How? How does this work? How is it possible to commune with God through Christ today? How is it possible to know the truth?

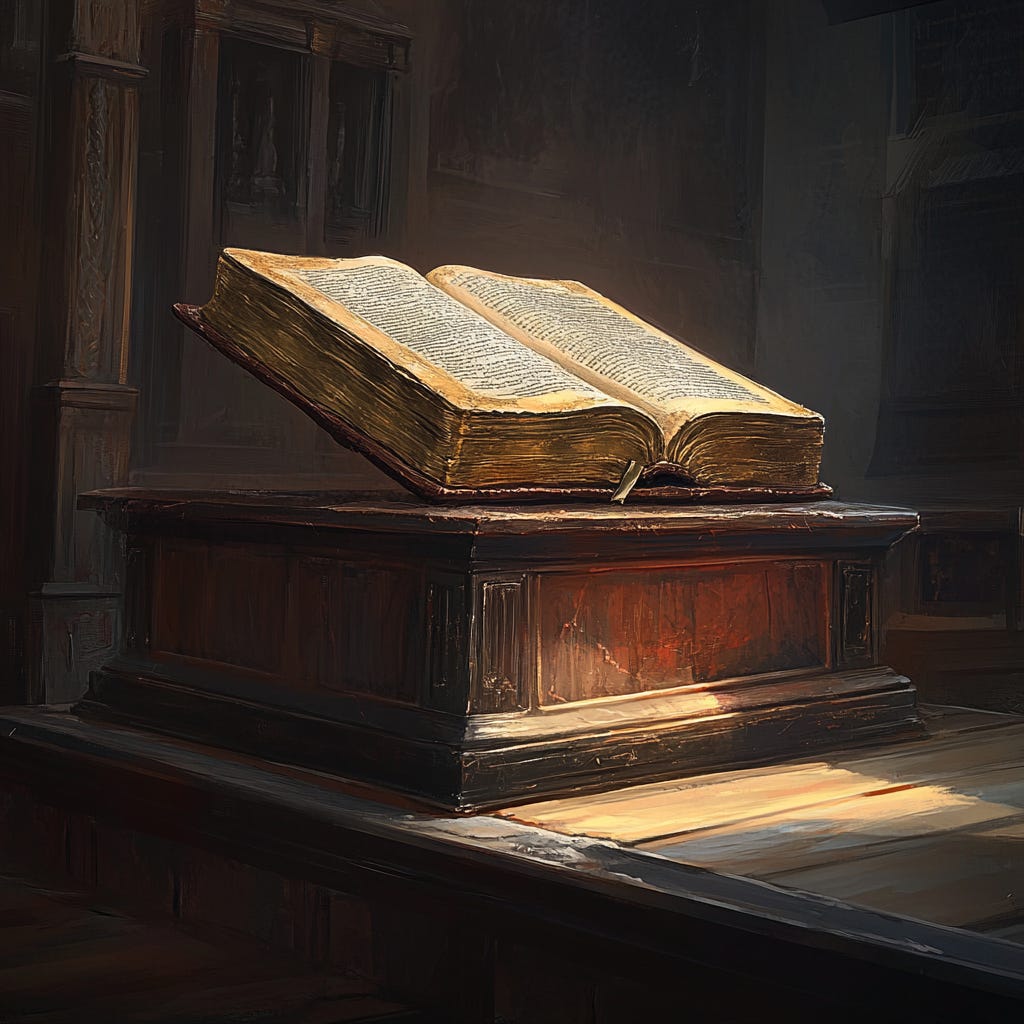

Simply put, the way in which we know Christ today is this: knowing Christ begins with the realization that God has anchored his redemptive revelation, centred in the man Jesus Christ, in the divinely inspired words of the Holy Scriptures. We saw earlier the way in which the word-revelation of the Old Testament was inscripturated, taking on a written form. Given that all the word-revelation pointed to Christ, and Christ is in fact the Incarnate Word of God, it makes perfect sense to say that – the written word-revelation of God is a revelation of Christ. As Paul Wells puts it: “Person and text go together” (Wells, Taking the Bible at its Word, p.26). When you read the Bible you are, as it were, hearing the voice of God speak to you. As God’s redemptive revelation unfolded throughout history, it was recorded for us in written form by divine appointment – to preserve this God-given revelation for future generations. For us today, the scriptures are therefore God’s revelation of Christ to us. They are God’s word to us, and they are likewise Christ – the Word of God – revealed to us. I will take another paragraph to open up this idea, because it’s very important.

We talked earlier about the historic character of God’s redemptive revelation, how he spoke and acted in various times, places, and ways. As we saw, his redemptive revelation was ultimately fulfilled and achieved in Christ. For us today, we come to know of these things through the holy and inspired records of those events which we find in the Bible. As Packer puts it: “The Bible is… the link between the revelatory events of the past and the knowledge of God in the present” (Packer, God Has Spoken, p.30). “The written Word of the Lord leads us to the living Lord of the Word” (Packer, God Has Spoken, p.20). Or, as Van Til potently expresses it: “Christ…speaks to us in Scripture” (Van Til, Doctrine of Scripture, 1). In a sense, then, Christ speaks mystically1 to us, through the ministry of the Holy Spirit (which we’ll get to a little later), through the words of scripture. The Bible is not just a book, it is the living medium through which we encounter the living Christ.

1 And by mystical I simply mean that this whole thing functions on the spiritual level in a way that is, to some extent, mysterious to us.

1 At the time of writing, it is ridiculously expensive online, you have to go to Greenville, South Carolina, for yourself and pick one up at Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary if you want it – or get a friend to do it for you! Update: it has since become available on amazon/kindle for $1! PTL!!

2 Article 2 of the Belgic Confession, for instance, answers this question by saying that we know God by two means: 1. (by His) creation, preservation, and government of the universe… (making) us ponder the invisible things of God; and 2. “He makes Himself known to us more openly by His holy and divine Word” (BC Art 2). WCF 1.I recognizes exactly the same two sources.

3 “Special revelation is salvific revelation” (Bavinck, Prolegomena, K.E. Loc 7114 of 18660).

4 Bavinck helpfully clarifies that “word,” or prophetic, revelation of God in the Old Testament should more broadly be understood as God conveying his thoughts to men. The prophetic word is the dominant carrier of his thoughts, but he often used other means – such as dreams or visions – to convey his thoughts. These too, according to Bavinck, ought to be understood broadly as falling under the category of prophecy. Bavinck’s discussion is quite useful and worth reading (Bavinck, Prolegomena, K.E. Loc 6855 of 18660 – see discussion on “Prophecy” under “Modes of Revelation”).

5 A theophany is a visible revelation of God to people.

6 The patriarchal period is the period of time when the “Patriarchs” of the Jewish nation were alive (e.g. Abraham, Isaac, Jacob…). It’s narrated in the book of Genesis, chapters 12 through 50. You would say that it ended with the death of Jacob at the end of Genesis. Scripture recognizes the unique place of the Patriarchs by frequently referring to God as “the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” They are the foundation of the Jewish nation, the men to whom God gave the great and mighty promises of redemption that would be realized through Israel.

7 Galatians 2:2 is one example of a revelation given to an apostle.

Share this post